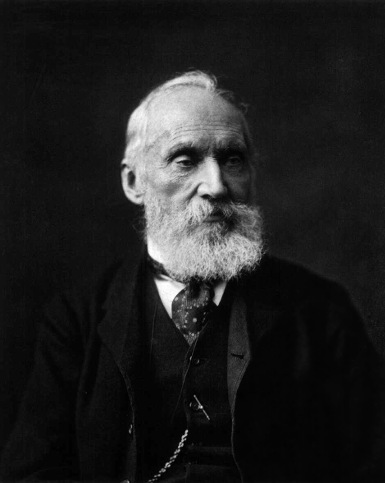

Lord Kelvin and the age of the earth

The story of how scientists revealed the age of the earth is a remarkable one; at the beginning of the nineteenth century many still believed that the earth had been around forever, but by the 1920s evidence from fields as diverse as geology and biology had been united, and the definitive source of the Sun’s heat discovered. Perhaps what makes the story even more fascinating are the egos and personalities that shaped it, and none more so than that of William Thomson, aka Lord Kelvin.

Lord Kelvin was arguably the most eminent scientist of his time, famous today for the temperature scale that bears his name. But it was his work on thermodynamics that led him to ponder the question of the age of the earth. He saw an opportunity to apply the recently formulated laws of thermodynamics to the problem, in particular the first law, which states:

The total energy of an isolated system is constant; energy can be transformed from one form to another, but cannot be created or destroyed

This is the principle of conservation of energy.

Kelvin sought to apply this principle to calculate the age of the Sun; he held the view that the Earth must have been formed after the Sun, and so by limiting the age of the Sun he could imply upper limits on the age of the Earth.

The Sun shines, and pretty brightly at that, so in assuming the principle of conservation of energy we imply that the Sun must have a source for this radiated energy. Kelvin’s theory for the source of this energy was gravitational contraction; when a body contracts under its own gravity it releases energy, and according to Kelvin it was this energy that powered the Sun.

We can calculate how much energy the Sun could possibly radiate if it collapsed from its current state with a little sixth form math and some Newtonian Mechanics.

Warning: If you are allergic to Maths, feel free to skip the next bit. You don’t need it to follow the story, but I’d certainly recommend running through it if you can; it’s a beautiful, if flawed, argument!

We first define the gravitational potential energy, $\Omega$, from Newtonian mechanics, as,

where $G$ is the gravitational constant, and $m_1$ and $m_2$ are two masses whose centres of gravity are separated by a distance $r$.

To apply this to the Sun, and calculate its total gravitational potential energy, we first model it as a series of concentric shells, each of radius $dr$.

In the above definition, for a single shell at radius $r$, $m_1$ is the mass of the star within radius $r$, and $m_2$ is the mass of the shell itself. We then integrate between 0 and $R$, the radius of the Sun, to add up the contributions from all of the shells, giving the total gravitational potential energy of the entire star.

Here, $m(r)$ is the mass within radius $r$, and $4 \pi r^{2} \rho dr$ is the mass of the shell. We are assuming that the Sun has uniform density, which is not the case but sufficient for such a back of the envelope calculation; Kelvin made the very same assumption when making his argument.

Now, rewrite $m(r)$ in terms of $r$ and $\rho$ to give

which, when integrated, simplifies to,

This can be rewritten in terms of the mass of the Sun, $M = \frac{4}{3} \pi r^{3} \rho$, as

So, we now have a value for the total gravitational potential energy of our Sun. But before using this to calculate its age, we need to invoke a new theorem. Kelvin’s argument relies on the fact that the Sun is radiating energy that comes from gravtitational contraction. The form in which this energy arises within the stars is thermal, through heating. The conversion of gravitational potential energy to thermal energy is not 1:1, but is in fact related by the Virial theorem, which states that the total gravitational potential energy of a body, $\Omega$, is equal to minus two times the internal thermal energy of the body,

So, only half of the total gravitational potential energy can be converted to thermal energy. The minus sign in the above equation is important when explaining why bodies appear to get hotter as they contract and lose energy. In our case, the total thermal energy within the sun is then,

We can now use this to calculate the age of the Sun! Given the luminosity of the Sun today ($L = 3.846 \times 10^{26}$ Watts), and assuming that this has stayed constant throughout the Sun’s life, the age can be given by the ratio of the total thermal energy against the rate of energy loss. Sticking everything in, we get

As we said previously, if we assume that the Earth formed after or concurrently with the Sun, then the Earth must be younger than this. This result contradicted those that believed the Earth had been around forever, and was one of the unsung successes of the theory today. Unfortunately, it is the value of the age itself that has become infamous.

In short, this age is nowhere near long enough; Geologists such as Charles Lyell had argued that the processes that shaped the Earth’s surface, such as erosion and uplift, required far greater timescales. In biology, Charles Darwin’s natural selection also required far greater timescales on which to act to account for the variety of species existing today.

Unhelpfully, rather than exploring these issues, Kelvin simply refused to accept them, and continued to argue that gravitational contraction could be the only source of the Sun’s energy, and therefore that the age of the Sun must of order millions of years, not billions. He called some of Darwin’s estimates ‘absurd’, and used Physics position as a more established and prestigious field than Geology (at the time) to bully its purveyors. This went on for nearly 50 years.

It took the discovery of radioactivity as an alternative heat source, both for the Earth and the Sun, to render Kelvin’s assumptions invalid and eventually rubbish his theory. There was now a far larger energy source available to power the Sun for the timescales required by Biologists and Geologists. In terms of the age of the Earth, plate tectonics and convection in the Earth’s mantle, in addition to further heating from radioactive materials, placed much greater lower bounds on the Earth’s age.

Radiometric dating of rocks also provided ‘bonus’ evidence, as rocks could now be shown to be far older than Kelvins initial results. Ernest Rutherford, a pioneer in radiometric dating, reveals a humourous encounter with Kelvin where he presented his early calculations:

I came into the room, which was half dark, and presently spotted Lord Kelvin in the audience and realized that I was in trouble at the last part of my speech dealing with the age of the Earth, where my views conflicted with his. To my relief, Kelvin fell fast asleep, but as I came to the important point, I saw the old bird sit up, open an eye, and cock a baleful glance at me! Then a sudden inspiration came, and I said, ‘Lord Kelvin had limited the age of the Earth, provided no new source was discovered. That prophetic utterance refers to what we are now considering tonight, radium!’ Behold! the old boy beamed upon me.

Lessons learnt:

- Don’t rely on your assumptions too much; even if your theory is simple and elegant; as the old adage goes, ‘rubbish in, rubbish out’.

- Don’t be arrogant and pompous; even if you are the first British scientists to join the house of lords, if your model is wrong you’ll end up with egg on your face. And in the end, all models are wrong, but some are useful.

Edit: the previous version of this post had the wrong sign for the thermal energy and all the grammar mistakes, thanks to Abi and Spyros for pointing them out

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: